I Broke Up With My Mother part three

In the final part of this three-part series, I share some of what I've come to understand about why it took until this year to permenantly end our relationship.

Parts one and two. Paid subscribers: Scroll down for the full audio of this post.

Within hours of closing the door on my mother and our relationship, I had to get a flight to Edinburgh for a work conference. Holding back tears while waiting to board the flight, I decided to write an Unsent Letter, something I’m a huge proponent of because you can use it to write out your feelings and process the past.

Everything she’d said that morning reverberated in my head, and my nervous system produced the usual tremors that I experience in the aftermath of these assaults. I needed to calm and soothe myself. It’s like when somebody pisses you off, and then, afterwards, you think of other things you should have said. “And another thing…” you argue to yourself in the shower… or in your journal.

Typing away on my iPad—I’d left my physical journal in my suitcase—I purged myself of every lie and distortion she’d thrown at me that morning. Reading my rebuttals to some of her accusations, I felt deeply ashamed of myself again. For the sake of having a mother and, on some level, wanting to be ‘better’, ‘different’, I’d delayed the inevitable. A part of me didn’t want to hurt my mother in the way she’d hurt me, but that’s a false equivalency. I can see that my mother hurts and struggles, but that doesn’t make, for instance, what she did to me as a child okay or make my having any boundaries now the same as it.

The shame engulfed me. It seemed pungent like everyone on the flight must surely know how bad and unworthy I was. And then I saw and felt Little Nat so clearly, and I realised I owed her an apology, not shame. She’d waited a very long time for me to remove the person from her life who’d made her feel the most unsafe in this world. Ever patient, ever reasonable.

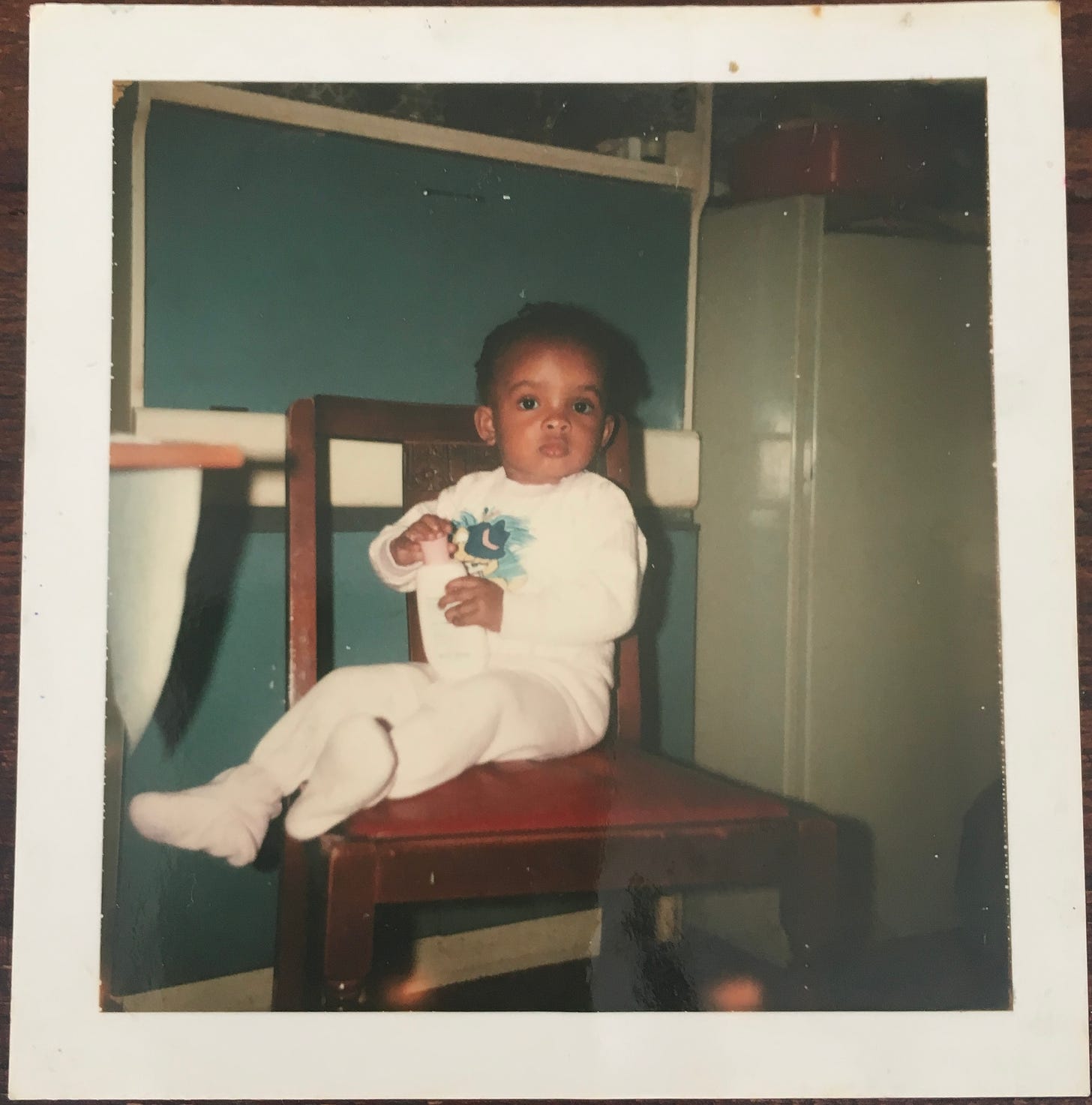

I hadn’t meant to, but I see now that I was still abandoning her by continuing my relationship with my mother despite the fact that she still saw fit to attack me periodically. That morning, what became abundantly clear is that very little’s changed about her. No growth, just shapeshifting. Whether I was a three-year-old on the high street in Wolverhampton or a forty-five-year-old in the spare bedroom of my home, my mother was still berating me for nonsensical betrayals while simultaneously displaying her betrayal and dislike of me. Enough.

If you’re wondering how my relationship with my mother lasted as long as it did, pause. It’s like asking, “Why didn’t you leave?” or “Why did you stay?” or “What were you wearing?” or “How come you didn’t say something sooner?”

Something I explain throughout my work, including in The Joy of Saying No, is that boundaries are wonderful and necessary when you finally embrace them instead of shaming yourself and others, but they’re not miracle workers. They don’t turn water into wine or make people spontaneously combust into entirely different people. So if you think you’ll Jedi mind trick somebody into having remorse, empathy, compassion, changed behaviour and whatnot, you’re not quite there with your boundaries yet.

Cutting people off to avoid conflict and the necessary work of evolving your boundaries won’t solve your problems either; they’ll just manifest in a different form.

It’s also, however, true that given that healthier boundaries come to many of us later in life, typically as a result of the pain of too much yes and self-neglect, they’re a work in progress.

But because boundaries are trial and error, it also means that sometimes you won’t see where your tendency to be reasonable, particularly around people who tend not to be, can obscure the fact that you’re trying everything else first before getting to the boundary you’ve always known, deep down, is the one to go with.

The more I knew myself, the healthier my boundaries were, the more I, my relationships and my life evolved, the less space I’ve had for my mother in my life.

Reflecting on the last eighteen years, in particular, since I experienced an awakening during a frightening health crisis and began consciously taking care of myself by what I later recognised as creating healthier boundaries, I see a gradual severing of my relationship with my mother. I’ve known for a long time that my boundaries, which are at any given point the embodiment of who I am, would no longer accommodate a connection with her.